|

By Mark Schaffer

TIME

Magazine and the

Deterioration of Liberty

ime is a flagrant example of publication by committee rather than by responsible individuals and by the time legmen, researchers, editors and writers get through pushing the facts around and making them conform to style rules, policy and individual bias, the truth has fled up the chimney.” So wrote columnist John Crosby about the perils of editorial news reporting at the weekly founded by Henry Luce.

Since Crosby penned those lines many years ago, case histories have proved him out time and time again and point up the need for genuine change at the publication once described by P.G. Wodehouse as “about the most inaccurate magazine in existence"—one whose recklessness with the truth has even endangered freedom of speech.

True Lies on the Internet

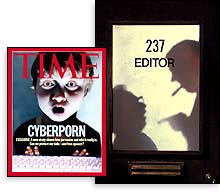

An April 1992 Time story on the Lockerbie disaster added to the storm of controversy around the magazine’s reporting. (See “Lies and More Lies”.) But that flap—and the others which preceded it—was overshadowed by the magazine’s July 1995 cover story on pornography on the Internet—one that helped to instigate legislation which many Net users see not only as an encroachment of First Amendment rights in cyberspace but as the government’s first saber-rattling threat to regulate the Internet.

The subject of the story was volatile. Obscenity on the Internet, as elsewhere, is a knotty issue. Few want smut to proliferate, but laws defining what is and is not obscene are usually prone to misinterpretation. Works by authors such as D.H. Lawrence, James Joyce and others can become suspect. Even more worrisome, other forms of free expression, such as political dissent, can be labeled “obscene” and subsequently stifled.

Time made the matter worse for the Internet community by trying to palm off a story about pornography in cyberspace that was riddled with almost as many faults as the Lockerbie piece.

The magazine’s sensational cover story claimed that the vast majority of images posted on the Usenet portion of the Internet were pornographic. With computer-literate children regularly accessing the Net every day, parents across the country were shocked.

Based entirely on a then-unpublished study done at Carnegie-Mellon University entitled “Marketing Pornography on the Information Superhighway,” it was touted as the work of a prestigious team of university researchers. Time had gained “exclusive rights” to publish the study.

Time made things worse for the internet community by trying to palm off an article about pornography in cyberspace riddled with almost as many faults as its earlier Lockerbie cover story.

|

|

The report was actually written by an undergraduate named Martin Rimm and was reprinted by Time without question.

Rimm asserted that 83 percent of all images posted to the Usenet were pornographic. To the reader unfamiliar with cyberspace, the Internet would appear to be little more than a running sewer of smut.

In truth, pornographic image files were found on only three percent of Usenet newsgroups. The Usenet is but one part of the Internet and represents only about 11.5 percent of the entirety of cyberspace. Grade school arithmetic would have shown any reporter or editor that less than one percent of the images which appear on the Internet are, in fact, pornographic.

The majority of these are only available on adult bulletin boards which charge fees, accept credit cards and usually demand proof of age, such as a driver’s license, before a person can download anything.

Government Clampdown on the Net?

The Carnegie-Mellon study—and along with it the Time story—quickly became a target for respected academics and Internet aficionados. Donna Hoffman and Thomas P. Novak, associate professors at Vanderbilt University’s Owen Graduate School of Management, did their own investigation.

“At some point, an agreement was negotiated in which Time magazine obtained an advance copy of the manuscript in exchange for an ‘exclusive.’ This was used in preparation of the July 3, 1995 Time cover story written by Philip Elmer-Dewitt,” they wrote.

“Given the vast array of ... flaws in this study ... Time magazine behaved irresponsibly in accepting the statements made by Rimm in his manuscript at face value.”

Time’s editors knew of these flaws in advance of publication. “Indeed, Time reporters were made aware that the study appeared to have serious conceptual, logical, and methodological flaws that Time needed to investigate prior to reporting its story,” said Novak and Hoffman.

“If Time was not able to evaluate the manuscript on its own, Time should have held the story until the manuscript was publicly available, so that expert opinion could have been solicited, or sought its own panel of objective experts for a ‘private’ peer review. In this way, Time would likely have recognized the study for what it was and not what it purported to be and prepared a balanced, critical report on the subject of digital pornography.”

In the “Cyberporn” story, the concept of balanced reporting was replaced by a different set of standards.

“Time presented, around lurid and sensationalistic art, an uncritical and unquestioning report on ‘cyberporn’ based on Rimm’s flawed study,” said Hoffman and Novak. “This has had the extremely unfortunate effect of giving the study an instant credibility that is not warranted nor deserved and fueling the growing movement toward First Amendment restrictions and censorship.”

So why did Time editors deliberately print something they never investigated?

Shoddy Reporting

Time’s article appeared as the 1995 Senate telecommunications bill, S. 652, was moving through Congress. That bill contained the Communications Decency Act, known as the “Exon bill” after one of its three authors: Senators Exon, Gorton and Pressler.

The Exon bill was aimed at clamping down hard on pornography on the Internet. Its opponents considered the bill overly broad and a threat to free speech.

Appearance of the Cyberporn article stirred public opinion on an already volatile issue and was even used to generate congressional support as language from the article was incorporated into the legislation. Had the Carnegie-Mellon study not been discredited, the bill might have slipped through, riding a wave of Time-created public indignation.

One might have expected the furor over the faulty Carnegie-Mellon study and Time’s shoddy reporting to have put an end to the bill. But it didn’t.

Black Thursday

On Thursday, February 1, 1996, Congress approved a modified version of the Communications Decency Act as part of a massive telecommunications reform bill. Included in the Act were stiff penalties for distribution of obscene materials to minors on the Internet, measures strikingly similar to the Exon bill.

But despite the laudable intentions behind the legislation, the Act still suffered the same flaws as its predecessor—it was overly broad and too easily subject to misinterpretation. A week later, on February 8, the bill was signed into law.

Response from the Internet community was instantaneous. More than 1,500 web sites turned their home pages black in protest. Sponsored by the Coalition to Stop Net Censorship, “Black Thursday” was supported by Yahoo, Netscape, the American Civil Liberties Union, the Electronic Frontier Foundation and many others.

President Clinton’s signature was scarcely dry when the Electronic Privacy Information Center, in conjunction with the ACLU and 18 other organizations, initiated a constitutional challenge to the Communications Decency Act by filing a lawsuit in federal court in Philadelphia on February 8, calling for a temporary restraining order.

On February 15, Judge Ronald Buckwalter, Jr. issued a temporary restraining order. He called the CDA “unconstitutionally vague” and stated, “This strikes me as being serious because the undefined word ‘indecent,’ standing alone, would leave reasonable people perplexed in evaluating what is or is not prohibited by the statute.”

On February 23, Attorney General Janet Reno agreed not to initiate investigations or prosecutions under the “indecency” or “patently offensive” provisions of the CDA. It was agreed the matter would go before a three-judge panel in Philadelphia to determine the constitutionality of the law.

Nearly four months later, on June 12, the specially appointed federal panel barred the government from enforcing the Communications Decency Act, ruling it to be unconstitutional.

Fact versus Fiction

In retrospect, Time’s misleading reporting hampered the ability of our lawmakers to enact fair and workable solutions to a social problem.

In the wake of the controversy, Time apologists glossed over the fatally flawed “news” story by trying to redirect attention to the “important debate” about the “problem of cyberporn.”

But few have been fooled by the shell-game shuffle. Time’s lack of integrity and its willingness to advance a hidden agenda at the expense of the truth remains an issue.

As matters stand, Time’s big lie has, by polarizing the opposing sides in this debate, only served to delay the finding of a reasonable solution.

To report unverified, false information as truth to millions of people is outrageous; to create national hysteria over a non-existent “cyberporn epidemic” is even more so. But to top it off with effectively aiding and abetting legislation which might have curbed freedom of speech places a would-be news magazine in a class of infamy all its own.

|

|