|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

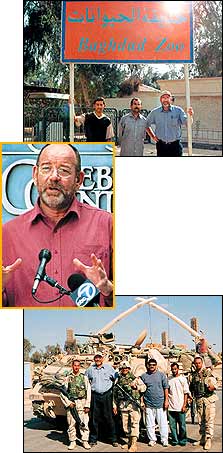

For Anthony’s mission was to save the inhabitants of the war-ravaged Baghdad Zoo and his story, told to LA Freedom Contributing Editor Linda Simmons Hight, is an inspiring one. And it is a continuing one that brought him half-way across the globe to Los Angeles, where on May 28, he announced the launch of a $1 million fund-raising campaign to achieve his goal. Through a consortium of support organizations and foundations, Anthony is confident he can do just that, and rapidly.

Lawrence Anthony’s story leaves no doubt why he has so rapidly garnered support from the American Zoo Association (including the LA Zoo), WildAid, the International Fund for Animal Welfare, the Scientology Environmental Task Force, the U.S. Army in Iraq and private individuals. Even before the Iraq war, he had made known to government officials of various countries who vacationed at his South African game preserve the certain fate of the animals in the famed Baghdad Zoo. As a Scientologist, he considers it his duty to safeguard and improve the conditions of all things living, and to enlist the support of others — friends, family and his community — to join him in such efforts.

As soon as the worst of the fighting was over — so he thought — he flew to Kuwait at his own expense and worked his way through Iraq. But even as he arrived in Baghdad, skirmishes still filled the air with the staccato of gunfire and the smoke from sporadic explosions and fires. Overcoming every “can’t be done” to gain authorized entry into war-torn Iraq as a volunteer administrator for the Baghdad Zoo, Anthony was the first civilian to be admitted. He was shocked at what greeted him: a squalid animal death camp abandoned by the Iraq regime and ravaged by looters. He found scores of dead or starving animals, locked in filthy cages to which no one had keys; hundreds of missing animals, likely stolen for food or for profit on the black market; and most of the zoo staff had disappeared. No water, power or food was anywhere in sight — neither for the animals nor the remaining three of the zoo’s 36 staff. (Not having been paid throughout the duration of the war, the other personnel had long since deserted.) He enlisted a team of local Iraqis and, with the support of U.S. forces, rescued and saw to the safekeeping of the ravaged zoo’s inhabitants, which had dwindled to half the population of lions, tigers, cheetahs — essentially any man-eaters the looters could not cart away with impunity. And captive dogs who had befriended the lions — so much so, says Anthony, they freely walked amongst the jungle kings. Undaunted by the continuing gunfire, he persisted in feeding, watering, cleaning the animals — and the zoo staff — with anything he could beg, borrow or “reappropriate,” in his words. “Some animals had to be fed to other animals,” he reported. “Locked cages had to be broken open, filthy animals and cages were scrubbed with disinfectant and precious water — when there was water.” Many animals had died, but many had somehow succeeded in their struggle to survive. Those near death in Saddam Hussein’s private zoos were located, rescued and pulled from the brink, then nursed back to health. Adding to the challenge were looters who, by the time Anthony had arrived, had stripped the zoo of every last scrap of equipment and material — door knobs, shovels, wheelbarrows, buckets, hoses. “I locked up the animal food to keep it from being carried off,” he said. “To protect the animals from returning bands of looters, the zoo staff and I started imprisoning them — as many as 30 looters on one particular day.” In desperation, the lessons of Anthony’s law and his “Baghdad Zoo Jail” worked. He and zoo workers held looters captive for a week, then released them. None returned. The U.S. Army subsequently posted guards throughout the premises and around the clock so Anthony could get on with his work. California: First to Send Aid

With the assistance of Stephan Bognar of San Francisco-based WildAid, Anthony started paying his zoo staff small amounts of money — mainly as an offering to keep them coming back to work. The salvage efforts then made international news, resulting in pledges of support from several animal welfare organizations and zoos in the U.S., including LA’s. The U.S. Army meanwhile provided supplies and materiel and transport for bringing the animals back to the main zoo from Saddam Hussein’s private enclaves. Shortly after his arrival in Baghdad, the Army appointed Anthony the interim administrator of the Baghdad Zoo. This nonpaid job was, said one observer, “all guts, no glory.” Yet, Anthony was visited at the zoo by General Garner, head of the U.S. forces in post-war Iraq, who noted, “Right now, this is the only functioning institution in Iraq.” The number of animals rescued is today but a fraction of the former population of 450. Nonetheless, conditions have improved dramatically and the zoo will reopen one day. But, says Anthony, his battle is anything but over. Reconstruction Era Anthony describes Baghdad’s 19th-century zoo as archaic — cramped cages with concrete floors instead of the clean, open, natural settings of today’s zoos. His vision for the future of this largest zoo in the Middle East includes bringing the Iraqi staff to Los Angeles for training under zoo staff here so that the Iraqis can return and transform their zoo into a humane, modern facility with maximum animal welfare and visitor enjoyment. And, with posterity in mind, the South African also established Iraq’s first humane society for animals, with an Iraqi veterinarian in command. He has since returned to Baghdad to continue his work. Later this year, he will return to the United States as the guest of the American Zoo Association for more speaking and fund-raising. One day, indefinite per his honest estimates, he will return to the game preserve he owns in South Africa’s bush. To contribute to the restoration of the Baghdad Zoo, the LA Zoo and the American Zoological Association ask that you send your donations to “Aid to Baghdad Zoo,” c/o North Carolina Zoological Society, 4403 Zoo Parkway, Asheboro, NC 27205.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Previous | Scientology Glossary | Contents | Next | |

| Your view | Scientology Related Sites | Bookstore | Church of Scientology Freedom Magazine |

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Supported Sites

Scientology Groups · Reviews for "The Church of Scientology" · Scientology: The Doctrine of Clarity · Religious Tolerance: Scientology · Description of the Scientology Religion · Scientology (CESNUR) · Scientology · Scientology Handbook · Scientology Religion · What is Scientology?