ou may be a stranger to the Internet, the main artery on the so-called information superhighway. You may not even know what the Internet really is or how it works. You may not even own or use a computer. But even if you don’t know a modem from a mouse, the Internet knows you. Probably better than you care to be known.

ou may be a stranger to the Internet, the main artery on the so-called information superhighway. You may not even know what the Internet really is or how it works. You may not even own or use a computer. But even if you don’t know a modem from a mouse, the Internet knows you. Probably better than you care to be known.

If you have ever applied for a driver’s license, worked for the government, gone to college, married, purchased insurance, paid taxes or even just seen a doctor, the Internet system of computer networks, often referred to as “cyberspace,” probably contains information about you — detailed information which you probably assumed was cloaked with some sort of privacy or limited in distribution to those for whom you volunteered the information.

Guess again. More likely than not, transactions involving you have found their way without your knowledge or consent to one or more of the thousands of computer networks linked through the omnipresent Internet.

The Internet may contain the most personal of records, such as those maintained by physicians and hospitals. Easy access to that data through computers is supposed to be good for the patient, by furnishing rapid availability in the event of an emergency far from home, quick test results, speedier diagnosis and treatment, and lower medical costs due to rapid exposure of fraudulent insurance claims and avoiding duplicative procedures.

But take the man in California who is neither homosexual nor HIV-infected, yet found himself the unwitting victim of a mistaken report in a computer database that said he was both. Through the Internet, the information was soon accessible to thousands of people and conceivably already in their hands before the error was discovered. Suddenly the spectre of discrimination was present and real, all based on falsehoods proliferated essentially automatically throughout the networks of the Internet. Almost immediately, he was unable to get health or disability insurance. Worse still, he is finding it impossible to get the false report expunged from the database and a correction issued. Even if he does succeed in deleting the false information, the falsehoods already have spread far and wide.

Easy access certainly has its advantages. A serious researcher can reduce by an entire generation the time involved ferreting out extant data on his or her subject. Scientific or humanistic results can be published years earlier because of the data retrieval features of the information superhighway. Lives can be saved, frontiers explored and global communication established.

Users in dozens of countries on every continent — even Antarctica — rely on the Internet as a computerized means to exchange information, receive and send electronic mail, transfer files, conduct business, obtain computer entertainment and news, keep track of their finances and their favorite television shows, shop for clothes, music and even food, participate in special interest computer discussion groups, and on and on and on.

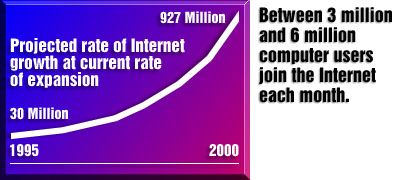

But the Internet’s promise of the information superhighway is tempered by perils and temptations for the unscrupulous. For decades, the abuse of computerized information has been of major concern to civil libertarians, and today, after such dramatic advances in both telecommunications and computers, the problem has reached Orwellian proportions. Damaging information can reach 30 million computer users in a matter of hours. Recourse, if any, is difficult, incomplete and often insubstantial.

For all its seeming complexity, the Internet is actually remarkably simple, and each month, between 3 million and 6 million computer users enter the network for the first time. If the telecommunications companies realize their goals, it will be accessible through home television sets in the very near future.

But just as television was not readily understood when it emerged from laboratories and into living rooms some 50 years ago, the Internet, which is unlike any medium seen before, can seem abstract and unfathomable to the uninitiated. But even as television redefined entertainment, the Internet is poised to redefine not only entertainment, but also information, communication and commerce. Even the way each of us conducts the routines of our daily lives.