How Psychiatric

Theories Spawned

Intolerance

Against Religions

By Timothy Bowles

n a Western country earlier this century, an established religion was condemned by certain psychiatric “experts” as inimical to the interests of the state and society. Among the claims leveled against this widely embraced yet minority faith was that with supposed absolute sway over its adherents, many known for their industry, the religion was intent on world domination through control of banking, commerce, politics, media, and the medical and legal professions.

Such “authoritative” analysis, repeated broadly through the channels of special interests, led to a public complacency that allowed this religion and its followers to be isolated, harassed and brutalized, actions upheld by courts in that country.

The inhumanity in Germany did not stop until millions had lost their lives and fascist control was removed by force of arms.

Of course, this could never happen in the United States. Or could it?

Borne on the arbitrary standards of “emotional distress” claims, which allow the seemingly unorthodox to be condemned by juries as “outrageous,” public pleas to segregate and diminish, if not destroy, certain religious faiths can and have been upheld by American courts, and in particular California courts, within the past decade.

In a 1988 case, for example, the California Supreme Court declined to extend constitutional protections to the Christian-based Unification Church in lawsuits brought by former members. It held instead that assertions by psychiatric theorists of church “brainwashing” — since rejected by other courts as incompetent evidence — could justify causes of action for fraud and “emotional distress.”

Such intrusion on the First Amendment rights of individuals to pursue their chosen faiths is part of a wider erosion of judicial protection of religious life over the past 20 years. This undermining reached the point where strict standards of constitutional review were set aside by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1990.

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA) was enacted with fanfare by President Bill Clinton and a host of political and religious leaders in hopes that it would renew protections of religious liberties thwarted by that 1990 decision. However, without an accompanying revolution in actual judicial recognition of minority religious rights — directed as necessary by further federal and state legislative enactments, particularly in California — the RFRA is unlikely to restore the neutrality and tolerance of spiritual diversity upon which this country was founded.

Pseudo-Science

Long before 1990, the “compelling state interest” standard was regularly undermined by the pseudo-scientific opinions of psychiatrists and psychologists, by the arbitrary standards of “emotional distress” claims, and by a judiciary which allowed the dissection of religious beliefs. With this trend likely to continue, it is now up to state and federal legislatures to build on the RFRA through further specific enactments to curb court-sanctioned bigotry and intolerance of lesser-known denominations.

Judicial condemnation of new and different practices on the basis of supposed “scientific” analysis is nothing novel. To the then-existing “authoritative” literature in the late 17th century in Massachusetts, Cotton Mather added Memorable Providences, a diagnostic manual on witchcraft. His checklist, which included criteria such as “broomstick rides” and “sexual relations with the devil,” was adopted by Governor Phipps’ special court, appointed to address accusations of widespread witchcraft in Salem.

By 1692, that court had hanged 14 women and five men. The frenzy did not stop until the accusations of witchcraft were aimed at distinguished citizens of Boston, including established clergy and the wife of the governor.

The First Amendment’s religion clauses, which are the culmination of long-standing debate on whether spiritual diversity would be a tenet of the American republic, are intended to guarantee that at least the new federal government could never sponsor such religiously motivated persecution: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof....”

Universal Religious Freedom: Cornerstone of a Free Society

“In a free government the security for civil rights must be the same as that for religious rights. It consists in the one case in the multiplicity of interests and in the other in the multiplicity of sects.... In a society under the forms of which the stronger faction can readily unite and oppress the weaker, anarchy may as truly be said to reign as in a state of nature.” James Madison |

Led by James Madison, universal religious freedom guarantees were identified as a cornerstone of a free society: “In a free government the security for civil rights must be the same as that for religious rights. It consists in the one case in the multiplicity of interests and in the other in the multiplicity of sects.... In a society under the forms of which the stronger faction can readily unite and oppress the weaker, anarchy may as truly be said to reign as in a state of nature.”

While the Constitution forbids federal religious discrimination, either for or against, until the middle of this century states were in effect left to their own discretion to oppress or support religious groups.

At least in theory, the fulfillment of Madison’s ideal of justice for religions appeared to be assured by the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1963 decision in Sherbert v. Verner. In this case, the “compelling state interest” standard was erected as a barrier against any attempted government regulation that affected religious practice. A state needed to demonstrate a “compelling” interest of sufficient magnitude to override First Amendment concerns of religious freedom.

The Sherbert decision protected religious objections to Saturday work raised by a Seventh-day Adventist.

This assurance was underscored by a subsequent case that granted Amish objectors an exemption from compulsory education at the high school level. The Supreme Court stated that only government “interests of the highest order” could prevail over genuine claims to free exercise of religion.

The court, however, has almost uniformly supported the government in cases of intrusion on religious practice since Sherbert. Indeed, it widened the scope of “compelling” state interest, while narrowing what was considered “objectionable government actions” that would improperly infringe upon religious rights.

As a result, controversial decisions have been handed down, as in 1988, where the court held that destruction of traditional Native American religious sites by road crews did not impose improperly on religious rights as the action did not have a “tendency to coerce individuals into acting contrary to their religious beliefs.”

Until 1990, minority religious belief and practice enjoyed a strict constitutional protective standard, at least in name. But that year this changed from the rule to the exception when the court abandoned its “compelling interest” standard by ruling that no longer could an “individual’s religious beliefs excuse him from compliance with an otherwise valid law prohibiting conduct that the State is free to regulate.”

While the government is today still required to maintain a “benign neutrality” toward religion, the growing judicial insensitivity toward religious rights reflected in these developments amounts to an unconstitutional governmental hostility toward religious beliefs and practices.

Erosion of Constitutional Freedoms

In some cases, lawsuits for intentional infliction of “emotional distress” against religions have carried this erosion of constitutional freedoms to absurd extremes with all the logic of a Salem witch-hunt. A growing body of professional and judicial commentary has questioned the utility of applying the loosely defined standards of this relatively new tort, based on the arguments of discredited psychological or psychiatric “experts,” to religious practices.

As the issue of liability in such cases rests on the jury’s determination of how “outrageous” or intolerable the accused party’s conduct supposedly was, damages in cases of intentional infliction are aimed at punishing the defendant, rather than the traditional aim of compensating the plaintiff. Because nothing presently stops a jury from likening what is “outrageous” to what is “unpopular,” juries are allowed to impose large verdicts since, as one legal scholar put it, “of who [the accused parties] are rather than what they have done.”

The danger of punishment of the unorthodox is high when religiously motivated conduct is involved because relative to the jury the religion involved is almost always “someone else’s” faith.

While at least the Ninth Circuit of the federal court system — covering California, Arizona, New Mexico, Nevada, Utah, Washington, Oregon, Hawaii and Alaska — has recognized the protective effect of the First Amendment in such intra-religious disputes, the same could not be said of many of California’s higher court decisions.

A handful of psychiatrists and psychologists fallaciously claim to possess the ability to distinguish between mainstream and non-mainstream religious indoctrination. And California’s senior judiciary has shown a particular unwillingness to accommodate minority religious faiths in this context.

For example, in 1987, an apostate of the Worldwide Church of God was awarded $260,000 in general compensatory damages and $1 million in punitive damages for defamation and “emotional distress” from a supposedly critical publication regarding her divorce.

The trial judge rejected the defendants’ First Amendment defense, a decision later moderated by the appeals court.

In 1988, in a case involving the evaluation of the effects of study of religious texts by a later-discredited “expert,” the California Supreme Court ruled that the Unification Church’s religious practices could be found to be unorthodox and thus “outrageous.” In contrast, similar decisions in other states have recognized that a religious basis for a defendant’s alleged conduct bars such suits.

According to Douglas Laycock, professor of constitutional law at the University of Texas, “The Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, Mormons and Jehovah’s Witnesses all began as unfamiliar, high-demand, proselytizing religions, greeted with deep hostility by more sedate and longer established faiths.”

Legislation Needed to Protect Religious Belief and Practice

| ||

|

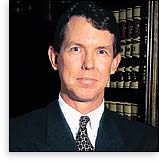

Timothy Bowles is an attorney in Los Angeles and a spokesperson for the National Commission on Law Enforcement and Social Justice. For more than a decade, he has specialized in litigation involving First Amendment religious freedom issues. |  |

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act is an encouraging step toward restoring the earlier, more vigorous standards of protection of religious freedom. But religious freedom will not be assured unless the contemporary trend of non-recognition of religious rights by the judiciary is reversed. It may well be up to legislatures to direct judicial protections of religious beliefs.

It has been the lawmaking branches of government that have consistently provided such shelter. Religious exemptions are provided in more than 2,000 state and federal statutes nationwide. For instance, Congress has provided a wide range of blanket protections and exemptions to religious practices.

In the face of consistent judicial unwillingness to extend its required benign neutrality to minority religions, the legislative branches of federal and state government must continue to build and repair the constitutionally based protections of sectarian belief and ritual against government intrusions condoned by the courts.

Recent “emotional distress” litigation in California, where religious practices have been condemned by the counterfeit science of mental health “experts” and found by juries to be “unorthodox” and therefore “outrageous,” demonstrate that the need for legislation to protect against modern-day versions of the Salem hysteria is urgent and essential.