|

by Thomas G. Whittle & Carlynn Lee McCormick

Deceit, dirty tricks and violence are destroying a Native American homeland, where traditional Navajo face a fate as dark as death itself.

n July 16, 1979, nearly 100 million gallons of water contaminated with 1,100 tons of uranium waste burst through a dam near the Arizona-New Mexico border and poured into the Puerco River, the primary water source for many Indians and their livestock.

It was the worst spill of radioactive material in United States history, but just one in a series of man-made cataclysms to beset the region and its inhabitants.

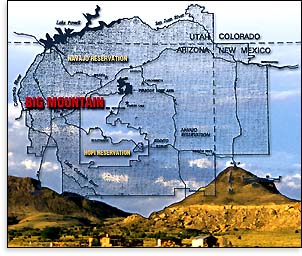

For centuries, the native Navajo and Hopi have made their homes in the Four Corners area, a rugged, wind-swept land of mesas, mountains and canyons, of sagebrush, cedars and pines where Arizona, New Mexico, Utah and Colorado meet.

The herding lifestyle of the Navajo harmonized with the farming Hopi, whose harvests were frequently exchanged with the Navajo for mutton and wool. Both peoples practice ancient religions rooted in the Earth itself.

In the midst of what had generally been a peaceful scene, the stage became set for a tragedy of historic proportions when a “land dispute” between the two tribes, fueled by commercial interests, resulted in 900,000 acres wrested from the Navajo in 1974.

Since then, some 12,000 traditional Navajo have been forced to sever their ties to their homeland — the biggest displacement of Native Americans since the 1860s and the nation’s largest enforced population removal since the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. Many were ultimately relocated to uranium-poisoned land on the Puerco River. Those who refused to move have faced multiple eviction notices, the bulldozing of sacred burial sites, confiscation and killing of livestock, legislation forbidding them to repair their homes and other harassment.

Despite ever-mounting pressure, hundreds of Navajo remain, devoted to their land and sacred spiritual sites that some say date to the 13th century. They have persisted in defiance of several federal ultimatums issued over the past 25 years to vacate their land — the most recent deadline passing on February 1, 2000.

The federal agency responsible, the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA), has not only failed to resolve the situation, but has exacerbated the stress and trauma on the native peoples involved through its actions and inactions. Freedom’s investigation furthermore found the bureau’s work compromised by factions in conflict with Indian sovereignty and well-being — an ugly fact of life confirmed in ongoing litigation brought by the Navajo Nation.

A Created Dispute

The Navajo land issue surrounds Big Mountain, which rises above a massive, mineral-rich plateau of roughly 4,000 square miles known as Black Mesa. In an area normally unseen by the legions of tourists that visit the Navajo Indian Reservation and the smaller Hopi Indian Reservation it encloses (see map, this page), Big Mountain is the center of ancient traditions for a proud people.

The mostly elderly Navajo who continue to live on or around Big Mountain raise livestock and maintain a traditional lifestyle devoid of computers, VCRs and other trappings of contemporary society — a lifestyle so elemental, in fact, that most have neither running water nor electricity.

Black Mesa has been estimated to contain 18 billion tons of high-grade, low-sulfur coal, much of it readily accessible within a few feet of the surface with a value estimated at up to $100 billion.

Commercial interests have long coveted the rich coal reserves. According to published accounts, beginning in the 1950s or possibly earlier, a Salt Lake City attorney named John Sterling Boyden sought the agreement of the Navajo to dig up their land and remove the coal. Mountains hold a special place in Navajo beliefs, among which is the conviction that sacred spirits reside in these lofty places. Unwilling to desecrate their holy land, the Navajo turned Boyden down.

Boyden then approached the Hopi, a tribe then sharply split between traditionals and non-traditionals. Since the traditional Hopi — the vast majority of the tribe at the time — refused to have anything to do with despoiling Black Mesa, Boyden founded a Hopi Tribal Council composed of non-traditional members.

Although the council Boyden formed originally had representatives from only a minority of the autonomous Hopi villages, he got it to file a lawsuit in 1962 on behalf of the Hopi people, seeking to obtain federal agreement that the Hopi possessed rights equal to the Navajo to the coal that lay on Navajo-occupied land on Black Mesa.

Boyden and his council prevailed, and in 1966, the council signed leases with Peabody Western Coal Company for Black Mesa’s coal. Evidently viewing the matter as a fait accompli, the non-traditional Navajo Tribal Council signed similar agreements.

The traditional Hopi refused to recognize Boyden’s Hopi Tribal Council or the coal leases which violated their sacred beliefs that the land must be respected and protected. Their attempts at recourse included appeals to President Lyndon Johnson and, later, Presidents Richard Nixon and Jimmy Carter to prevent mining on Black Mesa.

They filed a lawsuit to protest the leases, only to have it rejected on the reasoning that the council was a sovereign power, therefore the Hopi had no recourse to the U.S. courts. Because the Hopi traditionally register disapproval through silence, it is difficult to gauge the extent of opposition to Boyden’s tribal council. But even decades later, in the mid-1980s, four of the 14 Hopi villages were still not sending representatives to the council because they didn’t believe in it.*1

From the 1960s well into the 1980s, Boyden or his son-in-law, John Paul Kennedy, directed the council’s actions and policies, handling all negotiations for coal leases. Long before his death in 1980, Boyden’s many years of adroit lobbying and courtroom maneuvering had cut the ground from under the traditional Navajo and Hopi in Congress and the courts. At no time, however, did Boyden disclose that while posing as Hopi general counsel he was also working for Peabody — a serious conflict of interest.

|

|

A Navajo elder (above, bottom) stands at the bottom of a strip mine near her home. A human rights disaster underlies the story of Black Mesa (above, top).

|

|

Havoc on the Reservation

News accounts over the decades inaccurately portrayed the resistance of traditional Navajo and Hopi to relinquish their homes on Black Mesa as the intensification of a “land dispute” between the tribes. People such as Roberta Blackgoat, chairwoman of the Sovereign Diné * Nation of the traditional Navajo, tell a far different story. Blackgoat observes that Hopi and Navajo have lived side-by-side in relative peace for centuries, as attested to by Oraibi, a Hopi village on the southern end of Black Mesa, dating to 1100 A.D. and regarded as the oldest continuously inhabited community in the United States.

Blackgoat notes it was only in the past 50 years that major friction was manufactured as part of a plan to gain control of Black Mesa’s valuable mineral rights. And irrefutable evidence exists of political manipulation, dirty tricks and even violence as commercial interests have sought the resources that lie there. That effort has been directed primarily at removing the Navajo who occupy the majority of the mesa.

Ironically, the primary instrument in forcing the Navajo out has been the BIA, the agency responsible for protecting and advancing Indian rights and tribal resources. While the bureau’s mission statement is “to enhance the quality of life ... within the spirit of Indian self-determination,” its actions in the Big Mountain controversy — including confiscation of livestock and enforcement of laws that forbid even the most rudimentary repairs to Navajo homes and other structures — have torpedoed the traditionals’ quality of life while blocking their self-determination at every turn.

Arlene Hamilton, an expert on traditional Navajo ways who for nearly two decades has coordinated the Weaving for Freedom Foundation, an organization of Navajo weavers, points to the historic and religious significance of Big Mountain and the value of preserving the traditionals’ lifestyle. “These are the last Native American tribal matriarchs in North America that still have their language, culture, ancient art and ceremonial rites intact,” she told Freedom, “and everything is based on their ties to that land.”

While paving the way for evicting the Navajo, John Boyden worked hand-in-hand with a PR firm, David W. Evans and Associates, which also represented Western Energy Supply and Transmission (WEST) Associates, a consortium of 23 power companies.*2 The “land dispute” between the Navajo and Hopi was played up into a full-blown conflict between tribes, leading federal lawmakers to believe that it was actually in the best interests of the Navajo to move from the area.

Meanwhile, a climate of fear, accompanied by actual violence, enveloped the reservation. Although no links have been established to Boyden, the PR firm or Peabody in this regard, it has been alleged that incidents of violence were an integral part of efforts to evict the Navajo.

Running the Navajo off the Land

Between 1973 and 1975, for example, no less than 10 Navajo in the area of Farmington and Gallup, New Mexico, were tortured, mutilated and murdered — including one young victim who died after an explosive device was forced up his anus and detonated.

In the midst of the turmoil, Congress became convinced that land shared by the Hopi and Navajo for centuries had turned into the site of a bloody “range war,” and it passed the Navajo-Hopi Land Settlement Act in December 1974.

Efforts by traditional Indians and their supporters to stand up to their adversaries and either get the act rescinded or halt its enforcement often met violent ends. A prominent Navajo voice, Fred Johnson, who testified before the U.S. Civil Rights Commission against strip-mining on sacred land and condemned inherent health and environmental hazards, died in early 1976 in a plane crash, “the mysterious circumstances of which led many Navajo to conclude that he had been assassinated.”*3

Even the death of veteran journalist Don Bolles has been linked to Navajo matters. Six sticks of dynamite blew Bolles out of his late-model Datsun on June 2, 1976, the force of the explosion shattering windows hundreds of feet away. While the self-confessed hit man, John Harvey Adamson, was sentenced to prison, those who hired him have never been brought to justice. At the time of his murder, Bolles allegedly was investigating a plan “to create havoc on the Indian reservation,” reportedly aimed at destabilizing the Navajo tribal government of the then-chairman, Peter MacDonald, and fomenting an atmosphere in which mineral resources could be extracted at minimal cost.*4

As a consequence of the 1974 Settlement Act, over a period of years some 12,000 Navajo, many unable to speak English, were uprooted and relocated in strange cities and towns, deprived of their spiritual relationship with the land, and barred from returning to their ancestral homes. One of the primary relocation sites lay on the Puerco River — contaminated land obtained at discounted prices after the 1979 uranium spill.

Unprepared for radical lifestyle changes in an often hostile environment, many Navajo wandered off, homeless, while statistics of alcoholism, suicide and death soared.

*1 Benedek, Emily: The Wind Won’t Know Me: A History of the Navajo-Hopi Land Dispute, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma, 1999, page 30

* Diné is how traditional Navajo refer to themselves; it means “the People.” In a document signed by 64 elders on October 28, 1979, the Diné declared their independence from the United States, the Navajo Tribal Council and the state of Arizona.

*2 Kammer, Jerry: The Second Long Walk, University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1980, page 85

*3 Johansen, Bruce and Maestas, Roberto: Wasi’chu [The Greedy Ones]: The Continuing Indian Wars, Monthly Review Press, New York, 1979, page 62

*4 Bowart, Walter: Freedom: “Havoc on the Reservation,” August 1986

continued...

|

|