|

Challenging History

Making Peace

By George J. Mitchell University of California Press Berkeley Updated, First Paperback Edition, 2000

Reviewed by Marion Barnes

here is a scene in Charlie Chaplin’s film “The Great Dictator” in which the rulers of Tomania and Macaroni try to reach an accord. Comic negotiations ensue:

“You remove the troops, then I sign the treaty.”

“NO! You signa’ the treaty, then I remova’ the troops.”

“NO! FIRST you remove the troops, THEN I sign the treaty.”

This continues until the dictators start throwing food at one another.

In a way, this scene reflects the state of peace negotiations in Northern Ireland in 1996 when George Mitchell arrived, at the request of three governments, to chair those negotiations. Instead of a food fight, however, an impasse in Northern Ireland could mean bombings, rioting and the death of innocent civilians. The situation in Belfast, in fact, was beyond Chaplinesque. The opposing parties refused to speak to each other or, in some cases, to even be in the same room. Disagreement over a Protestant parade route ended in rioting. Random shootings for unknown reasons, with equally mystifying retaliations, were the order of the day.

|

|

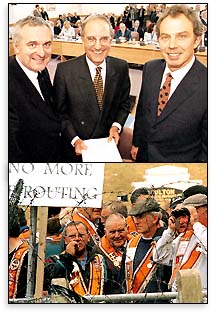

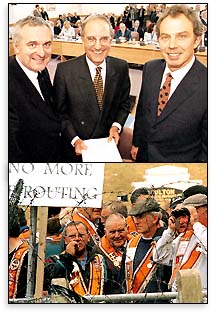

In negotiating the peace accord, former Senator Mitchell (top photo, between Irish Prime Minister Bertie Ahern and British Prime Minister Tony Blair) demonstrated that persistence can solve even the most complex and difficult of political situations. Above: Protestant marchers stand behind barbed wire blocking their path through a predominantly Catholic area in July 1996, shortly after the start of peace talks.

|

|

It was George Mitchell’s task to maneuver past the hatred, the political rhetoric and lies, and to get these stubbornly opposed factions to talk to one another. It was a daunting task which took diplomacy, determination and endless patience. Making Peace is the story of those efforts, which finally resulted in the Good Friday Agreement — the first real plan for peace in a land that has known nothing but violence for more than a century — and of Mitchell’s subsequent work to make that agreement a political reality.

Mitchell, who served as U.S. Senator from Maine between 1980 and 1995, the last six years as Senate majority leader, was commissioned by President Clinton to organize a conference on trade and investment in Northern Ireland in 1995. The job was to take a few months, after which Mitchell planned to take some time off from public service to be with his family. But Mitchell ended up spending most of the next three years involved in the peacemaking process in Ireland, first as a trade commissioner, then as chairman of the plenary sessions of the peace negotiations. These were the sessions attended by representatives of all political parties in Northern Ireland and the governments of Ireland and Great Britain. It took almost that long to get the main players to the negotiation table — to get them talking, if not to each other, at least to George Mitchell. It was a monumental accomplishment.

In Making Peace, Mitchell leads us through the maze of Irish politics. It is not an easy subject, but Mitchell does his best to make it comprehensible. Nothing in Northern Ireland, it seems, is simple. The religious factor is certainly a part of it, but the alphabet soup of political factions in Northern Ireland is complex and confusing. There are several Unionist parties (those wishing to remain united with Great Britain), Republicans (those wanting a united Ireland) with an entire spectrum of views in each. Each faction has a radical/violent wing loathe to give up their arms. Each has a leadership struggling to gain or to retain power. Each is connected through generations of hatred and defiance.

It took months and many battles for the parties to agree on who would be allowed to participate in the peace talks in the first place. It then took months for them to agree on how the talks would be conducted, and many more months of argument over the agenda. (They could not even agree on what they would talk about, if they ever did decide to talk to each other.) At times, Mitchell himself wanted to give up.

“The book makes it clear that to preserve and extend the peace, more communication, not less, has been and will be the answer.”

|

|

But through all of the politics and diplomacy involved, Mitchell kept communicating — through delay after delay, through the subterfuge of those whose vested interests lay in destroying the peace process, through attacks on his reputation and his staff, through every illogic known to man.

When finally it became clear that he was going to keep communicating, and that the governments of Britain and Ireland were going to keep pushing for an accord, the peace talks went forward. An agreement was drafted and redrafted. Deadlines were set and expired. Mitchell had to keep the opposing parties talking, try to meet each deadline set by the governments, keep presenting key points and beg the leaders not to leak the agreement to the press before it was completed to avoid further discord.

Up until the day the accord was signed, it was touch and go whether violence would erupt and shatter the lengthening period of peace and destroy hopes of a settlement. On the final day, only the Ulster Unionist position was in doubt, but they were the largest unionist party in Northern Ireland, and one of the four parties with veto power over any agreement. They were still meeting to decide whether to vote yes or no on the accord. Rumors abounded, as Mitchell explains:

“Their delegates were badly divided, shouting at one another; they were working it out. They were against it; they were for it. David Trimble, their leader, was in control. Trimble had lost control. The meeting would be over soon; it could go on all day.

“I could no longer tell fact from fiction, reality from rumor. So I waited, tired and nervous... a no would have profound adverse consequences. Many more people could die.”

But the intention for peace proved too strong. On April 10, 1998, the Good Friday Agreement was signed. Mitchell made the announcement:

“[T]he two Governments, and the political parties of Northern Ireland, have reached agreement. The agreement proposes changes in the Irish Constitution and in British constitutional law to enshrine the principle that it is the people of Northern Ireland who will decide, democratically, their own future.”

George Mitchell, his associates and the leaders of Ireland and Great Britain had brought a degree of sanity and hope to a troubled area. The Good Friday Agreement was then put to a referendum — the first all-island vote in 80 years.

“85 percent of those who voted said yes.... It was, by any measure, an impressive affirmation of the agreement. More than anything else, it is that overwhelming public support, freely given in an open, democratic election, that instills in me the hope that the Troubles are over.”

In the preface to the paperback edition, Mitchell notes that for a year and a half after the Good Friday Agreement, there was little progress toward its implementation. Then, in late 1999, Mitchell conducted a review of the peace process at the request of the British and Irish governments.

“The review was expected to last three weeks,” Mitchell writes. “It lasted three months. Eleven political parties were involved, four of them Unionist parties opposed to the agreement. ... At first their leaders were hostile and the meetings harsh and angry. But as we spent hundreds of hours together in long, searching discussions, they gradually began to move into serious negotiations.”

Important progress followed, Mitchell notes, including positive statements by the principal protagonists, Sinn Fein and the Ulster Unionist Party, as well as the transfer of authority from the British Parliament to the new Northern Ireland Assembly and the creation of new institutions agreed to on Good Friday.

“The people long for peace,” he writes in the preface to the latest edition. “They are sick of war, weary of anxiety and fear. They still have differences, but they want to settle them through democratic dialogue. ... They want and deserve a society of mutual respect and tolerance, of justice and equality, of peace and reconciliation. Let us pray that they will have it in the new millennium.”

Making Peace is a challenging book from many perspectives, and one of the notions it challenges is that man’s violent history cannot be changed. It demonstrates that persistence and communication can create agreement in the most complex and difficult of situations. In a lesson learned through years of effort to end the violence in Ireland, the book makes it clear that to preserve and extend the peace, more communication, not less, has been and will be the answer.

|

|